The monarch butterfly (Danaus plexippus) is an easily recognizable and much loved North American insect, and winter is a great time to see it in select eucalyptus or cypress groves along the California coast.

Fascinating migration

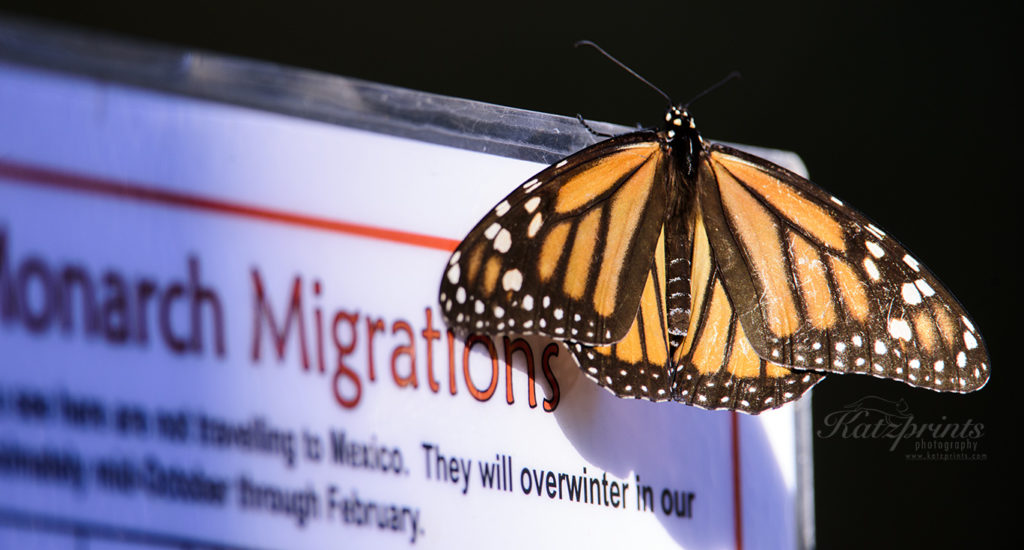

This butterfly species, with its beautiful orange wings, is the only butterfly known to make a two-way migration just like birds do. And what a complex migration it is! First, three countries are involved in the migration: Canada, the US, and Mexico. Thankfully, no passports are required in the effort. Monarchs that live on the eastern side of the Rocky Mountains migrate to Mexico; monarchs from the western side migrate to California. What’s even more fascinating is that unlike birds, who repeat their migration flights year after year, butterflies do not live long enough to take advantage of their own “memory”. As a matter of fact, it takes several generations of monarchs to do the round-trip. The migratory generation of monarchs heading south from Canada has the longest life-span with up to 9 months. It covers the whole southern trip, using air currents and thermals to fly 2000-3000 miles to their overwintering locations. I guess that is the reason why these butterflies often look quite disheveled. In early spring, these same butterflies initiate the journey back towards Canada. They become reproductive again, lay their eggs, and start the first of 3 or 4 much shorter-lived generations that are needed to make it all the way back to Canada.

Overwintering sites

If you live in the Bay Area, you are in luck because there are two overwintering sites relatively close by. In Santa Cruz, the official Monarch grove lies within Natural Bridges State Beach, clusters may also be found at Lighthouse Field State Beach. In Pacific Grove, check out the Monarch Butterfly Sanctuary. Further south, another nice grove is in Pismo Beach. For a complete overview, visit the Xerces Society.

When it is cold or windy, the monarchs huddle in clusters hanging in the trees and look unassumingly like bundles of dry leaves. But when the day warms up, flashes of orange start to hit the clusters as the butterflies pump their wings and start to drop out of the warming congregations.

Declining populations

The first time I visited the grove in Santa Cruz, the overwintering numbers peaked at 120,000 butterflies. A few years ago, the population at that same grove was under 500. According to the Xerces Society, the numbers of the western population have declined by a dizzying 99% since the 1980s!

While there are some natural causes to fluctuation, the most impactful factors of monarch decline are loss of overwintering habitat in Mexico, loss of natural habitat/way stations on route, pesticides, and climate change, which messes with thermals and creates extreme weather conditions. In addition, recent wildfires destroyed several overwintering sites in California.

What can you do?

Create a pollinator-friendly garden. A lot of nurseries can help you find plants that attract butterflies. They often come with the bonus of attracting hummingbirds and bees as well. Monarchs rely on “way stations” and even your backyard can add to the success of their migration. According to the Xerces Society, the plants you choose should ideally bloom in early spring (Feb-Apr). If you live near the coast, find plant that bloom in winter (Nov-Jan). Check out this plant guide for more info by region.

Plant milkweed. The milkweed is the only host plant monarchs lay eggs on and the only plant the larvae will eat. No milkweed = no monarch butterflies. One caveat: make sure the plant site is more than 5 miles inland from overwintering sites. Milkweed does not naturally grow close to the coast north of Santa Barbara. Milkweed too close to overwintering sites can interrupt natural monarch behavior.

Don’t use pesticides such as Roundup and make sure that the plants you buy have not been treated with neonicotinoids!

And lastly, go and enjoy this true wonder of nature.